Occasionally, I come across a book that was made with me in mind. Figures du Corps: Une Leçon d’Anatomie à l’École des Beaux-Arts is the catalogue of the exhibition by the same name held from October 21, 2008 to January 4, 2009 at the l’École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris. (Painfully, I first learned about the exhibition after seeing this book in a bookshop window in London, which is either a testament to my own ignorance of events like this or a sign that marketing efforts had limited reach.)

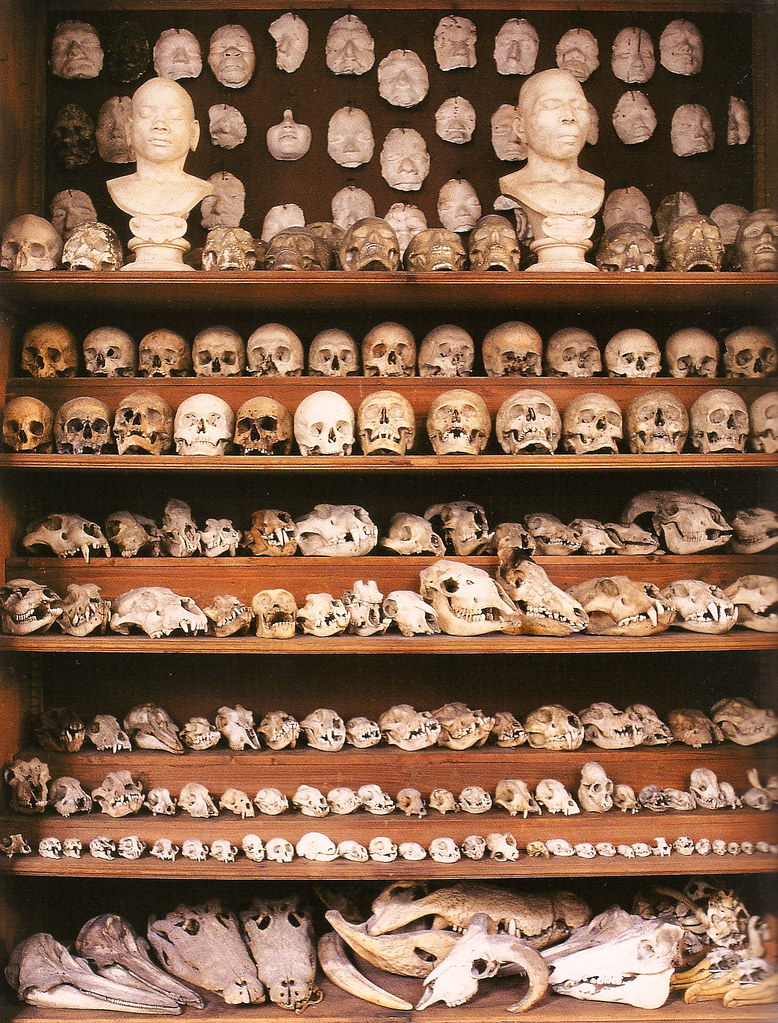

The catalogue is an ode to the bewildering and wonderful arsenal of contraptions, tools, plaster casts, photographs, and any other useful aid created to assist artists in the study of human and animal figures.

Resembling part medical research facility and part life-science museum, the Ecole des Beaux-Arts gathered human and animal anatomical examples–ideal, real and atypical–for use in training.

For artists at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, academic training meant mastering the human figure. As described in a previous post, this training took place over a series of graduated steps, beginning with isolating parts of the human figure, to studying idealized forms in Greco-Roman statues, and, finally, working with live models.

The catalogue includes several examples of classical forms that have been worked over to reveal underlying skeletal and muscular structure. It is evidence of a startling lack of superficiality in their approach to their craft and art. There are numerous accounts of dissections of both humans and animals, and visits from surgeons to discuss recent medical discoveries.

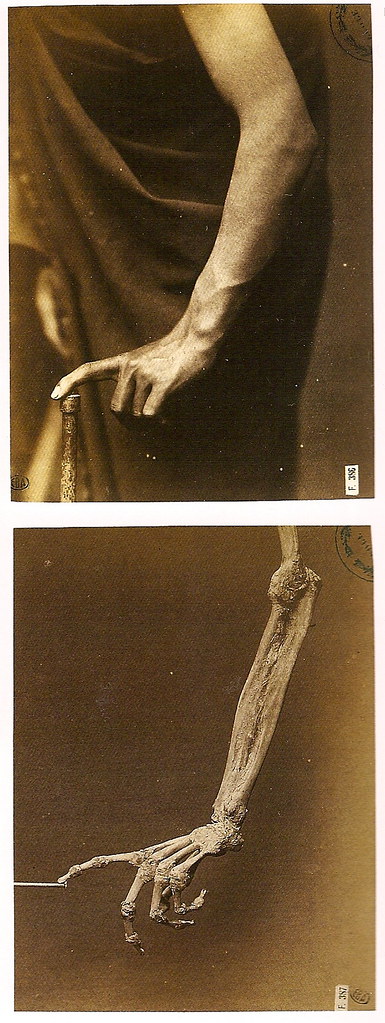

Looking at examples of plaster casts from the book, I was surprised at how many of them were obviously taken from human subjects and not from statues. The catalogue is unclear as to when many of these casts were made and used. Regardless, it is fascinating to see that they went to great lengths to articulate hands and feet in a wide range of challenging positions that were not always quoted from classical forms.

One of the greatest costs in training was the hiring of live models. As a result, contraptions of all kinds–mannequins, photographs, stereoscope images–were made to substitute, or perhaps more accurately, supplement, models.

One man at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, Paul Richer (Chartes, 1849-Paris, 1933) was particularly skilled both as a creator of artist aides and as a sculptor himself.

His work Tres in Una, above, is a terrific example of the late-nineteenth, early-twentieth century combinations realist and classical approaches to art. There is disappointingly little written about Richer in the catalogue, yet he is clearly one of a rare breed, simultaneaously gifted at educational innovation and a talented artist in his own right. For one, I would love to learn more about him, and hope to.

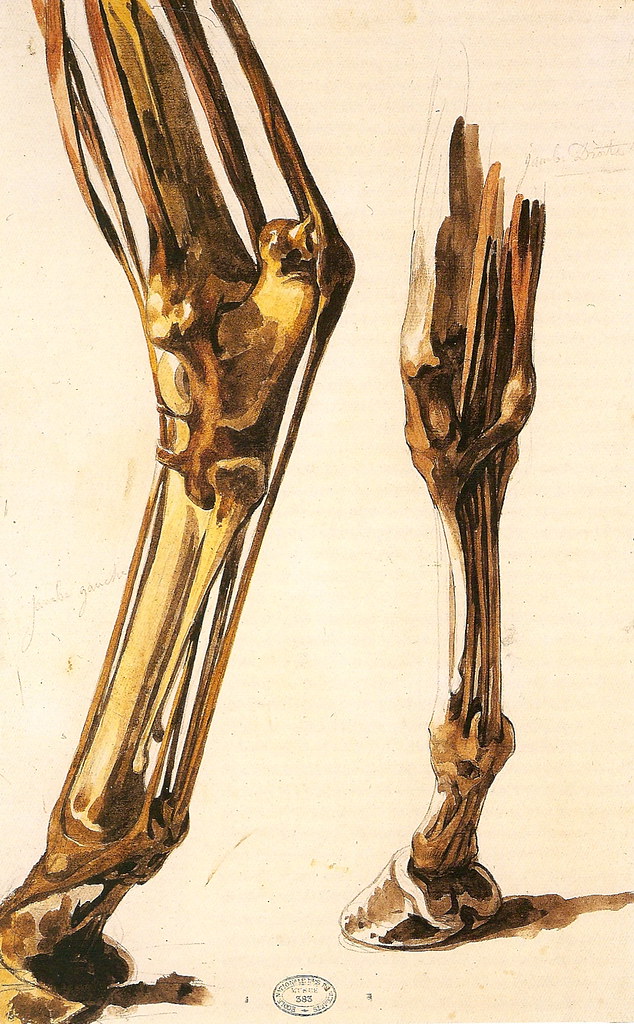

A great deal of the catalogue is dedicated to the anatomical models of animals, especially horses Just as in England, where George Stubbs (British , 1724-1806) led a generation of artists at the Royal Academy to explore and correctly understand the anatomy of horses, the French Academy invested a great deal in equine models.

One stunning example of an artist using the models is a study of horse legs, below, by Théodore Géricault (Rouen, 1971-Paris, 1824).

This catalogue makes it possible to comprehend the lengths to which artists would go to learn their craft. For me, it is both an inspiration and a reminder of how much we can learn from them.

An incredible post. Thank you for sharing. (Found via bibliodyssey’s shared feed.)

Great post. Your last sentence said it all.

A pleasure to see another 19th century master, i have never heard before. François Sallé. It’s unbelivable that a google search shows only one picture of him (or am i blind?). Another example of a totally underrated and neglected 19th century academic artist.

Roman, how perfectly gorgeous! Thank you. Something tells me no one’s going to that show in Paris to sneer at how bourgeois and backwards-looking the artists and their professors were. There are smart people who are never going to like academic painting, but thanks to efforts like yours, they might come to respect it rather than scorn it. Or, to feel a bit small-souled when they persist in their scorn. Either way, it works for me!

I thought that that painting looked familiar. It always stands out to me when I walk through; though until now I had not paid much attention to who the artist was. The collection of nineteenth century art in the Gallery of NSW is, in my opinion, the highlight of the entire place.

Thank you so much for this illuminating post. Is there any way to purchase 2 copies of this catalogue? Thank you for your help!

Laura, I’ve spent about 30 minutes looking for copies that can be bought through a US bookstore. But, unfortunately, I can’t find one. I bought my from Koenig books in London (http://www.londontown.com/LondonInformation/Shopping/_Koenig_Books/37cd/). If you find another option, I’d love to hear about it.

Fascinating subject, if only mannequins like that were still being made and sold!

I feel like I may have already asked you this in a previous post Mr. Christensen (if so, sorry), but have you in the course of your research heard anything about the fate of the Ecole des Beaux-Arts collection of casts? I’ve been told that a lot of them were vandalised and destroyed in the chaos of ’68. If so a real loss, but it would be nice to have some scholarly verification of this old atelier rumor.

That’s a great question. I don’t remember you asking it, but maybe I missed it. It’s true that in the 1968 riots, a number of things were destroyed. I have heard similar accounts of the castes in Russia during the October Revolution. I don’t know the answer to how much was destroyed in Paris, Brussels, or Berlin. That’s something I’ll look into.

[…] de la estructura corporal. La enseñanza de la pintura y de la escultura, pero sobre todo la enseñanza de estas disciplinas en el ámbito de las Academias de Bellas Artes instituidas a lo largo de todo […]