In several of my posts, I have pressed the importance of drawing. But it is important to know that not all the greats drew. One artist, in particular, who did not was Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez (Spanish, 1599-1660). Simply known as “Velázquez,” he was the greatest painter in the history of Spain and admired everywhere by academic and non-academic painters alike.

As mentioned in a previous post, Leon Bonnat, who became Director of the Ecole des Beaux Arts, regularly sent his students to Mardrid to study Velázquez’s works. Thomas Eakins said he was the “greatest painter who ever lived.” Painters as diverse as Millet, Manet, Sargent, Degas, Courbet, and Whistler admired and studied Velázquez’s paintings. They alll may have been surprised to learn what modern technology has taught us about Velázquez’s working method.

We know of only about 100 paintings by Veláquez, 45 of which are kept in the Prado Museum in Madrid. There, they have undergone chemical analysis of his pigments and a barrage of tests to show what lies under the paint. In the book Velázquez: The Technique of a Genius, Jonathan Brown and Carmen Garrido publish some of these findings.

Velázquez does not seem to have started with a fixed idea for a composition, but rather preferred to see what happened as he worked, making adjustments as he painted . . . The contours of figures overlap as their position in the composition changes or as elements are added or subtracted. Even within the forms of individual figures changes can be observed. The positions of hands and sleeves are adjusted, collars and lace are shifted, as are other parts of costume.

Landscape and neutral interior backgrounds were added, generally speaking, after the contours of the figures had been established.

(Jonathan Broan and Carmen Garrido, Velazquez: Technique of a Genius. (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1998), p. 18.)

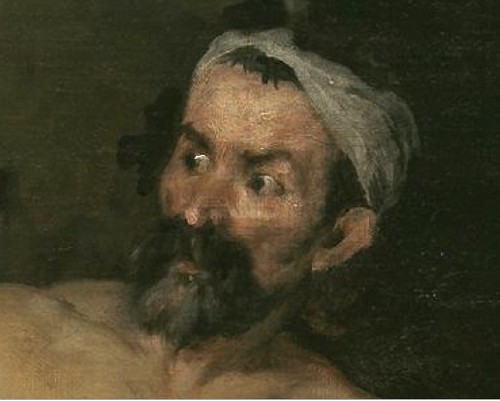

One of my favorite paintings by Velázquez, The Forge of Vulcan, is a good example of this improvisational approach. Originally, the head of Vulcan, the older man in the left-hand side of the painting, was turned away from Apollo.

To the left of Vulcan’s head, we can see a dark patch of brown paint where the back of his head used to be. In addition to this change, Velázquez enlarged the canvas. Over time, the pieces that were glued on became separated from the original piece and lines on the left and right of the canvas have become visible (See the first image.)

Not having drawn out the composition before hand, Velázquez created more work for himself. At the same time, it allowed him to go where his creativity led.

The results are stunning.

Obviously, drawing isn’t everything.

Wow! Thank you!

In traditional Japanese painting, which also doesn’t exist apart from drawing in the Ingresque sense, they make the distinction between line to which color is added, and imagery built through juxtaposing areas of color. So the whole conceptual framework accounts for an appearance that could never be mistaken for that of Western painting. But it looks like Velasquez was actually form-finding with his brush — this is godly and moving to contemplate. And it may account for two particularly dazzling markers of a Velasquez painting. First, the beautifully judged distances, with the eye being given only enough information to take in what’s happening, and no over-painted areas leaping out from too far away, to poke holes in the overall resolution. Second, the uncanny way animal or human hair grows — now we know that it did indeed arise organically, not as an add-on.

Funny Annemarie

I had my Xmas early at my mums cos my sister was headed to perth, from Sydney Via Melb, welll it was just easyer…

My dog Peppers last, she has now passed away, on the 23rd …

but

My mum, gave me some books and one was Velasquez,

and last night I was looking at another art book

French Painting in the Golden age by Christopher Allen,

page40

Antonine, Louis and Matthieu Le Nain

Venus in Vulcans forge,

and the forge

another version of this same picture with Venus in it,

very Intriging,

will further investigate,

Merry Xmas to you and your Family…

That Velasquez didn’t draw isn’t exactly true. There are a couple of excellent drawings attributed to him, one of which is highly finished. While the attribution of these drawings is subject to debate, there’s no question he considered linear accuracy in his paintings to be very important, much more so than, say Rembrandt. The fact that he evidently adjusted the contours of his figures shows not so much a disregard for drawing, but simply that he drew as he painted. That he achieved such compositions as The Forge of Vulcan without preliminary sketches seems hard to believe, but it’s possible. It’s a shame so little biographical information on him exists. One of the greatest, that’s for sure.

Thank you for your thoughtful comments.

You are right. There is a great deal of evidence that Velázquez drew, and we have excellent drawing by him. Looking back at my post, it seems to suggest that his work jumped from his brain, fully formed and on to the canvas. What I was hoping to reflect was what Jonathan Brown’s–long-time author and, perhaps, one of the greatest Velázquez scholars–surprise at the results of radiographic analysis of Velázquez work which show no underdrawings, grids or drawing transfers on key works. To Brown, the lack of these practices was uncommon for the time and especially surprising given exactly what you point out: his work is extremely linear.

I usually do not comment on blog posts but I found this quite interesting, so here goes. Thanks!

dong phuc mam non

Drawing Is Not the Only Way to Paint (e.g. Velázquez) | BEARDED ROMAN