Since I am now here in Madrid I do not regret at all my coming. I have seen big painting here. When I had looked at all the paintings by all the masters I had known I could not help saying to myself all the time, its very pretty but its not all yet. It ought to be better, but now I have seen what I always thought ought to have been done & what did not seem to me impossible. O what a satisfaction it gave me to see the good Spanish work so good so strong so reasonable so free from every affectation. It stands out like nature itself. [sic.]

-Thomas Eakins, in a letter to his father, Benjamin, dated December 2, 1869.

Saying that everything he had seen before “was pretty” but “not enough” is surprising. Eakins had just left the studio of one of the greatest painters of his day, Jean-Leon Gerome (French, 1824-1904), and lived in Paris, then capitol of the art world.

Eakins’ trip to Spain was a watershed for his personal development, and an indication of the draw Spain had for many painters working in Paris.

At the time Eakins visited Spain–during of the Winter of Spring of 1869 and 1870–it was considered a backwater, years behind civilized Europe in the arts and economics.

Yet, Eakins and a number of other important artists (e.g.. Eduoard Manet, Mary Cassat, John Singer Sargent) traveled to Spain works by Spanish masters in the Prado Museum. In 2003, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, featured an exhibition on French artists in Spain. Titled Manet and Velázquez and with 200 works, the exhibition discussed a newfound love of Spain that grew out of the French invasion by Napoleon’s armies in 1808 and the Mariage of Napoleon III to, Eugénie de Montijo, a Countess of Spanish Royal blood.

Eakins travelled to Spain shortly after the country’s government was overthrown. Despite the chaos, he was able to visit the Prado Museum and a number of galleries throughout the country.

He was especially impressed by the work of Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez (Spanish, 1599-1660). Eakins claimed Velázquez’s painting, The Weavers, was “the most beautiful piece of painting I have seen in all my life.”

“Here is how I think the woman tapestry-weaver was painted . . . [Velázquez] drew her withouth giving attention to the details. He put her head and arme well in place. Then he painted her very solidly without seeking or even marking the fold of the draperies, and perhaps he sought his color harmonies by repeated painting over, for the color is excessively thick on the neck and all the delicate parts . . .”

This kind of careful attention to technique was absorbed into Eakins’ own work.

According to M. Elizabeth Boone, author of Visitas de España: American Views of Art and Life in Spain, 1860-1914, it was shortly after seeing these that Eakins made his first original painting: Carmelita Requeña . In it, Eakins mimics Velázquez’s subtle use color and shadow, using very closely-related tones and small gradations of light to dark.

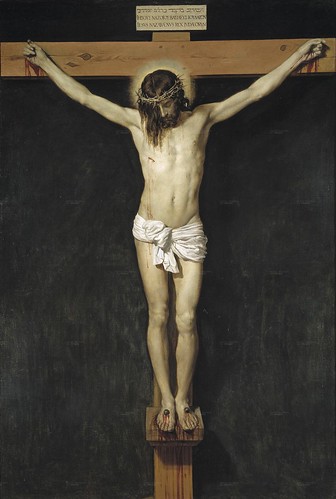

Besides, The Weavers, Eakins was inspired by Velázquez’s Crucifixion, painting a version of his own.

In the past decade, a great deal has been done to re-assert the influence of Thomas Eakins and France on American painting. With that in mind, it would seem necessary to explore the role of Spanish painting on these painters.

A fascinating perspective — thanks! I had not known about Eakins and Velasquez. But it could almost be inferred from his portraits — the gravitas of his sitters, or, his representation of them, owes much more to Spain than to the more usual American/French link. In the late 1970’s, there was a show going around — “The Face of Liberty” — which documented the influence of a trip to France on Benjamin West & Co.; what was added by that exposure was finesse and drama, the usual provincial lacks. If the influence of Spanish painting a century later could be assessed in an analogous show, maybe we would see an infusion of soul and “bottom.”

As usual, your thoughts add a great deal. I’ll look up the exhibition on Benjamin West.

I hope to write a lot more on the blog and in professional journals about the French/Spanish connection. Though some is written, we’ve only seen the tip of the iceberg.

[…] As mentioned in a previous post, Leon Bonnat, who became Director of the Ecole des Beaux Arts, regularly sent his students to Mardrid to study Velázquez’s works. Thomas Eakins said he was the “greatest painter who ever lived.” Painters as diverse as Millet, Manet, Sargent, Degas, Courbet, and Whistler admired and studied Velázquez’s paintings. They alll may have been surprised to learn what modern technology has taught us about Velázquez’s working method. […]

[…] mentioned in a previous post, Leon Bonnat, who became Director of the Ecole des Beaux Arts, regularly sent his students to […]

I just found a copy of “The Weavers”. This was purchased from the Van Pelt Art Galleries. It has a name of Ulla Britt Heijer, Madrid, Spain. It says By Velasquez – Copy of Painting in Prado Museum. Does anyone have any information about this copy? It would be interesting to me. Thank you so much, Rowena Tank, Prescott, Arizona

[…] Museum, where it hangs next to Velázquez’s Las Meninas (c. 1656). I know I have written about Eakins and Velázquez before, but I haven’t been able to stop thinking about the Spanish Master’s influence on […]