Eating in a London café can put you shoulder to shoulder with fascinating strangers. A few weeks ago, I was eating at an Italian restaurant in South Kensington, around the corner from the Victorian & Albert Museum. I overheard a conversation between a museum curator and a Russian journalist about the English language. The ideas they shared could have application for those who are interested in maintaining a classical painting tradition.

The curator must have been in his early sixties and had the kind of impeccable British accent that indicates a certain education. He was being interviewed by a journalist with a thick Russian accent, who was doing a feature on the Victoria & Albert Museum. Throughout their conversation, it was obvious that the journalist’s–a twenty-something woman–grasp of English left her struggling with many of the difficult words he was using. (They would have been difficult for many native English speakers.) Her frequent pauses for clarification took them from the topic of the interview to a discussion on the English language. The curator launched into what sounded like a well-rehearsed and delightful lecture on the “three pillars of English.”

“Words,” he said, “should be treated like endangered species.” He continued:

Whenever I find a word that has fallen out of favor, I write it down and make a conscious effort to use it and, then, reintroduce it as best I can. Such efforts, though minimal, are not insignificant. They breathe life into a dying language

“Dying language?” the journalist asked, “Isn’t English more dominant than ever?

This is when his thoughts lifted off the ground. He explained his theory:

English is based on three pillars:

- The Classics in Greek and Latin;

- The Annotated Version of the Bible [King James Version] ;

- And, Shakespeare

Once we loose an understanding of these three things, the language founded on them will die.

He went on to explain that no one learns Greek and Latin anymore, let alone the English translations of the books they once read in Greek in Latin, except for cursory school assignments at a young age. He lamented the loss of religion, and said that it seems that only a small number of enthusiasts are interested in Shakespeare today.

It was a cynical view of English and, after having talked with a linguist friend of mine, a view of language that is not widely shared by linguists. However, I don’t think it can be dismissed, and it seems to have application for a more than just language.

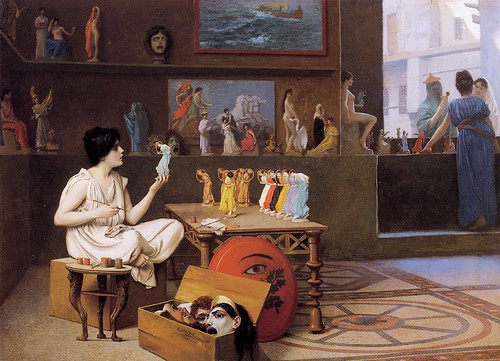

There is a rising generation of artists who are attempting to reinstate Academic painting, last practiced in earnest in the nineteenth century and most notably taught in the French Ecole des Beaux-Arts, the English Royal Academy, and the Spanish Escuela de Bellas Artes de San Fernando. These schools, for the most part, followed the same model which was based on similar pillars as mentioned by the curator.

I am in the process of researching the Spanish Academy in Rome, where the best-of-the-best of the rising generation of Spanish artists were sent for their final training between 1873 and 1913. Artists were sent to Rome by the government for three years. During the first year, they were required to copy an Old Master painting or Greek or Roman sculpture. For the second year, they studied the human figure. The third and final year was meant to combine all their skills in the production of a large history painting with its narrative drawn from religious or classical texts. The paintings would be sent to international competitions and, eventually, purchased by the State for the beautifying of public spaces.

These values in their education have a great deal in common with the curator’s three pillars and can be summarized as:

- Understanding of the Classics in the form of Greek and Roman statuary and architecture, based on ideal proportions, combined with studying Old Master paintings (e.g. Raphael, Titian)

- Narratives, provided by the Bible or classical texts, which provided widely shared, commonly understood and richly interpreted views of human nature.

- Observation of Nature

All three of these have been present in painting since the Renaissance. Should anyone continue to reinstate the technique of artists in the tradition, in my opinion they must also have a grasp of these foundational pillars; or, at least, a strong substitute.

Now, that’s and interesting thought. I’m not an art historian, nor do I play one on TV, but I typically make fun of modern art, because I can’t get over the suspicion that often there is no technical ability present.

Glad you’re back! Looking through the younger artists on the Art Renewal Center site — people in their 20’s and 30’s who are committed to getting as close as they can to the aesthetic of Gerome, Meissonier, Bouguereau & Co — do you see any who’re interesting for reasons other than an extraordinary level of skill at representational painting? To my eye, a fetish finish does much to detract from the interiority of a painting. One reason why Degas is a genius and Meissonier a dazzling technician is that the kind of precision Degas was capable of has absolutely nothing to do with fussiness; it is unerring, it is rapid, it is vivid. Compared to this, lots of academic painting truly has a mortuary feel. Oh, not all — I like and admire most of it. But comparing Degas to the academicians of the mid-19th century is not the same as comparing young avant-gardists of today with their peers in age who are technically capable of reviving academic painting and committed to that course. What I want from them is the sense that they have some reason beyond the exercise of technique to be painting, and I haven’t gotten that.

By the way — what do you make of the kitsch painting site? I’m serious…

http://www.worldwidekitsch.com/

And so are they….

You bring up a very important point. I absolutely don’t think that most of today’s artists are as interested in compelling work, like Degas, as they are in resurrecting technical know how. I think that many of the artists are content with the business they are getting because they are simply different from other contemporary, non-academic artists. In my experience, those buying these artists’ works are not demanding more than technical skill

I had a conversation with Jacob Collins, who could be considered one of the principles leaders in reinstating Academic techniques. I asked him why all of his figures are painted without context (e.g. backgrounds, props, narrative). His reaction was that he was returning to the Greek and Roman ideal human form seen in ancient statues. My response was that Greek and Roman statuary are of heroes and gods; therefore, they had context. He agreed then said: “I guess I haven’t determined my narrative yet.”

I think it took a great deal of humility on his part to admit that. I admire him for it.

In sharing this story, I don’t mean to suggest that I am more intelligent than Collins. In fact, for most of the time we were together, I was clearly out of my depth. He is brilliant.

His lack of narrative suggested to me that the Classical Tradition, as he calls it, is still in its beginning stages. Stage one seems to be: get down the technique. Step two should be: have something compelling to say with it.

As for dead artists in the academic tradition, I do find Degas more compelling than most Academic painters that you mentioned. But, I think that we remember the academic painters that the Impressionists loved to hate. We remember them because the created such a strong contrast with Impressionism. There are a number of Academic and academic-turned-realist painters I prefer to Degas: Dagnan Bouveret, L’Hermite, Sotomayor.

As for http://www.worldwidekitsch.com, I’ll check it out and get back to you on it.

I’m grateful for your comment.