The youngest son of the powerful Duke of Sutherland, Lord Ronald Gower (British, 1845-1916) was educated at Eton and Cambridge. He distinguished himself as a popular politician, serving in the British Parliament from 1867-1874. Following his political career, Gower became an unlikely, critically-acclaimed sculptor and an historical writer. In the words of his mother, the Duchess of Sutherland, Gower had “a certain unpractical side of his character.”

Gower’s first serious attempt at sculpting was, ironically, for his mother’s grave in 1868. He collaborated with Matthew Noble (British, 1818-1876) who was hired for a memorial befitting the Duchess. Noble was the son of a stonemason who studied sculpture in London. Chronically ill from childhood, Noble nonetheless exhibited regularly at the Royal Academy’s annual exhibition until he died at the age of 58. Though Gower mentions Noble as a major influence in his artistic development, the ex-politician was largely self-taught.

Untrained and unmotivated by financial gain, Gower was derisively considered a “gentleman sculptor.” Despite all this, his work received international critical and popular praise. Gower’s sculptures were accepted to the Paris Salons of 1880 and 1881, the Paris International Exhibition of 1878, and numerous competitions at the Royal Academy, placed alongside sculptures by Alfred Leighton.

The first public sculpture by Lord Gower was Marie Antoinette (1876), completed two years after his retirement from politics. Eight years later, Gower published Marie Antoinette: An Historical Sketch (1885). Both the sculpture and the book were part of a larger late-nineteenth-century reexamination of Marie Antoinette’s reputation. Gower’s works joined a chorus of scholars who asserted that the Queen was a scapegoat of unrestrained revolutionary fervor.

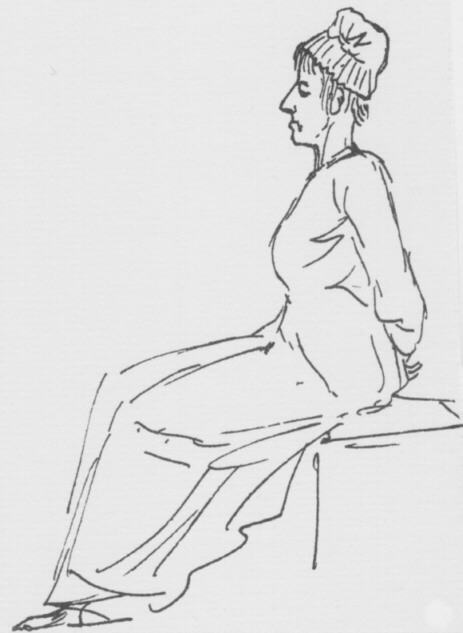

During French Revolution of 1789, angry mobs successfully captured King Louis XVI and Queen Marie Antoinette. The King was quickly executed, while the Queen was kept under arrest, where she reportedly refused to eat or move. In the weeks that followed, révolutionnaires cast Marie Antoinette as the personification of Royal excess and frivolity. Her fate became a national debate. During a two-day show trail, filled with unsubstantiated accusations of gross immorality, Marie Antoinette refused to defend herself, saying “If I have not replied it is because Nature itself refuses to respond to such a charge laid against a mother.” Fearing rising sympathy for the deposed Queen, the Revolutionary Tribunal cut short her trial. A mother of four and 37 years old, Marie Antoinette was publicly and summarily beheaded on October 16, 1789 at 12:15 p.m. The incident was famously captured by Jacques-Louis David, a passionate supporter of the revolution–in his humiliating sketch of the Queen on the platform of the guillotine.

Lord Gower’s sculpture Marie Antoinette (1876) preceded his biography by nine years, indicating the subject had preoccupied him for some time. Gower depicts the deposed Queen being led to the guillotine. With hands tied behind her back and hair shorn to elicit further humiliation, the deposed Queen walks forward, resolutely and unbowed.

The work is not a technical masterpiece. Anatomically it is more stylistic than correct. Like so many of the the artists featured on this blog, there are very few examples of Gower’s work available for public view and almost no images to speak of. However, Gower’s last work, Hamlet (1888) is perhaps his best and most memorable.

In 1883, the city of Stratford-Upon-Avon commissioned Lord Gower to create a memorial to the city’s most famous citizen: William Shakespeare. Gower worked for five years at his own expense. (In his memoirs, Gower claims it cost him an average of £500 per year, which he never charged the city.)

Though he lived another 28 years, Lord Gower declared the monument his last work and never sculpted again.

Really fascinating, thanks so much for posting this. Is it just me, or is there a little bit of the wonderful haughty disdain of Degas’ sublime “petite danseuse” in her pose and expression?

After reading this I found his Wikipedia article which brought up his homosexuality and even a disapproving letter from the Prince of Wales(!)regarding an association he belonged to, that was evidently notorious for its “unnatural practices.” Tuke of course was famous for his homoerotic paintings of sunlight dappled boys (not to reduce him to that solely, his, er, “All hands to the Pumps” was always a favorite of mine when I lived in London, marine light has never been so spectacularly captured).

http://www.tate.org.uk/servlet/ViewWork?cgroupid=999999961&workid=14530&searchid=24069&tabview=image

I recall Gabriel Weisberg mentioning that Tuke belonged to some sort of social club for those engaged in the love that dare not speak its name. Not to be too trendy here and engage in both Victorian social history and queer studies, but they must be the same association no?

IN A PAINTING I HAVE MARIE ANTOINETTE HAS HER HANDS TIED BEHIND HER BACK AND IS WALKING UP SOME STEPS WITH GOYA’S BROTHER-IN-LAW WATCHING FROM BEHIND.

Although very interesting I found this post riddled with historical innacuracies about the French Revolution and Marie Antoinette (I do not know enough about Lord Gower to verify the ones about him). First of all, I am pretty sure the French Revolution did not take place in 1889, but in 1789, (understandable typo). Second, the royal family was not captured from Versailles, they were forced to move to the Tuileries Palace in Paris where they were under surveillance by the National Guard. King LOuis was not quickly executed, in fact, it took them 3 years and declaration of war against Prussia for the National Guard to take to trial and declare him guilty and ready for the guillotine. Lastly, I don’t think it would have been possible for Marie Antoinette to not move or eat from the time she was taken away from Versailles until her death considering this was a span of 4 years, not weeks.

Just trying to helpful,

Thanks

It’s been years since I wrote this. Looking at it now, there are a lot of typos. Thanks for pointing them out. I’m embarrassed they have been sitting there for so long. I’ll fix them.

This is all most interesting. In 1875 Gower produced a terracotta bust of Marie Antoinette on her way to execution. George Augustus Sala wrote about it in The Illustrated London News (23 October 1875) and said he hoped to see it in marble. It was cast in bronze and a copy of it is in the Royal Collection., dated 1875 on the base.