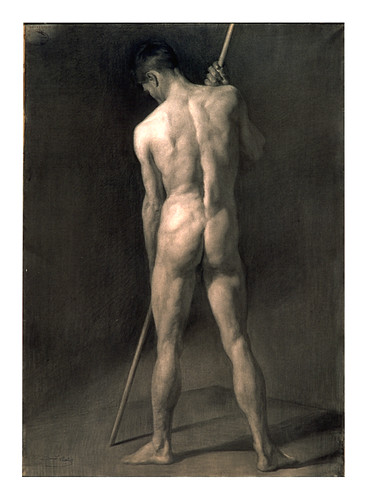

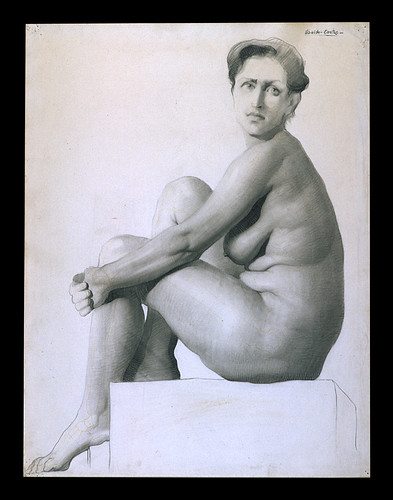

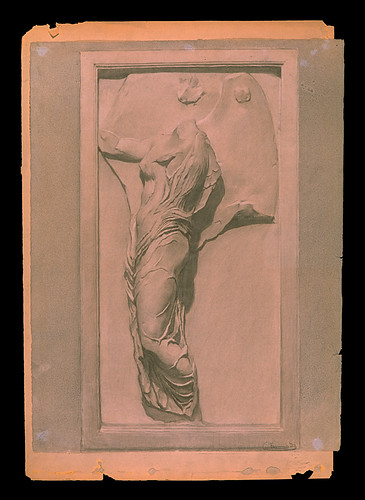

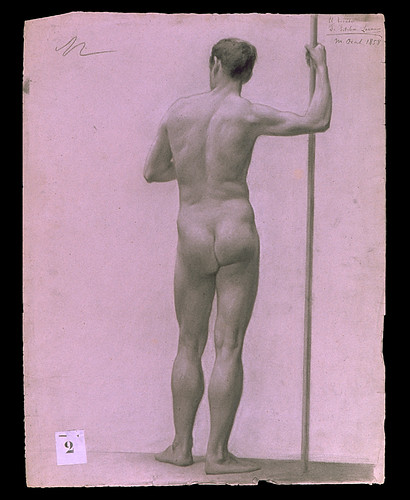

(All of the drawings in this post are by eighteenth and nineteenth-century students of the Academia de San Fernando. I am extemely grateful for the help of the brilliant Angeles Vian Herrero, Director of the Library of the Facultad de Bellas Artes of the Universidad Cumplutense in Madrid. These and many more drawings are available at a new website she has created for them. For larger versions of each image in this post, please click each work.)

Nineteenth-century art academies all over Europe used drawing as the foundation for art education. As I have noted before on this blog, Jean-Dominique Auguste Ingres (French, 1780-1867), once said “Over three quarters of what constitutes painting is comprised of drawing. If I had to put a sign above my door I would write: ‘School of drawing,’ and I’m sure that I would produce painters.” (It was not until the mid-1860s that oil painting was taught at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, where Ingres had been the director from 1825-1841. His approach to artist training was adopted in Spain’s most important school for artists, the Academia de San Fernando de Bellas Artes in Madrid.

The Academia de San Fernando de Bellas Artes was founded in 1752. Based in Madrid, it was one of several art academies in Spain (other cities with academies included Barcelona, Valencia, Zaragosa, and Seville). By the mid-nineteenth century, the Academia de San Fernando had become the dominant art academy in Spain and the model for art education throughout the country.

The Academia de San Fernando, founded in 1751, was heavily influenced by French-trained artists. One family in particular, the Madrazos, dominated the Academia de San Fernando for most of the nineteenth century. José de Madrazo (Spanish, 1781-1859), court painter for Ferdinand VII, was sent to Paris to study with Jacques-Louis David (French, 1748-1825). José’s son, Francisco de Madrazo y Kuntz (Sapnish, 1815-1894) was trained by Jean-August Dominique Ingres (French, 1780-1867) in Rome, and would serve as the Academia de San Fernando’s director from 1866 to 1894. José’s other son, Pedro (Spanish, 1816-1898), was the director of the Prado Museum, as well as a prominent art critic. All three were influential in setting standards and tastes for the Academia.

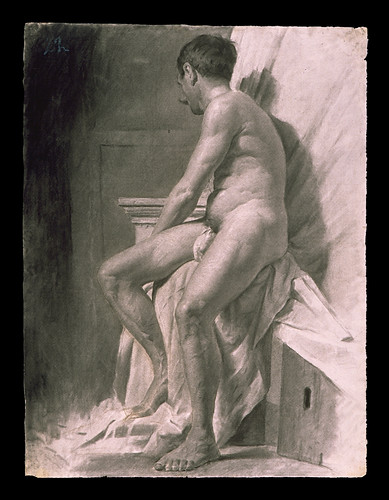

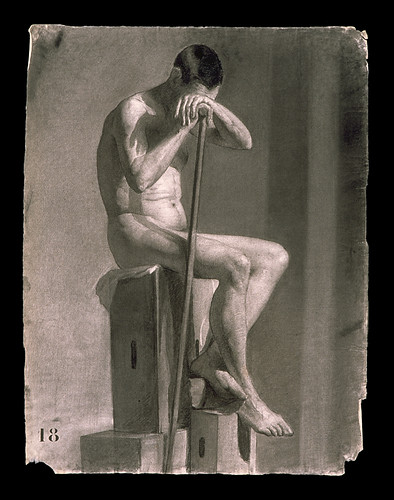

As in Paris, students in Madrid’s arts academy studied, on average, for four years. Some went on to receive scholarships and study at the Spanish School in Rome. (Established in 1873, the Spanish sent winners of an annual competition on the equivalent of the French Prix de Rome.) Students at the Academia began by drawing from castes of isolated portions of statues. Then, they were allowed to study from full statues of classical origins, either from castes made of the Spanish Royal collection or from collections in Rome or Paris. Advanced students, were allowed to study from live models, who were often placed in the poses of classical statuary or from scenes in Old Master paintings. As the century progressed, classical poses increasingly gave way to more natural poses and depictions of the human figure.

The majority of the works featured here are of nude men. This is because, in nineteenth-century Spain, there were strong cultural taboos against female nudity, even classical nudes. As a result, Spanish artists privately hired female models for their studio work as opposed to using them in official schools.

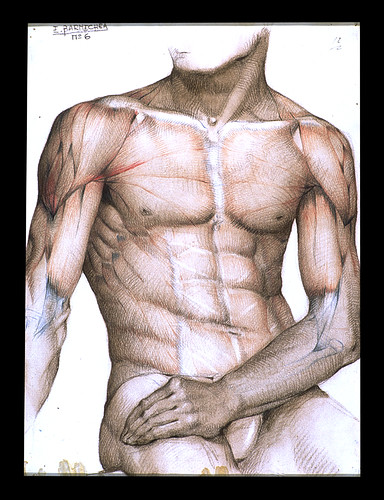

Some of the works perserved in archives are anatomy studies. Many of theses seem to be copied from books while other appear to be made from looking at live models and perceiving underlying muscle and bone structure. This is interesting because models were expensive. Using them for anatomical studies shows how important the Academia considered these studies.

How fascinating! Was not Fortuny a Madrazo via his mother? that would carry this family forward into the theatre and textile arts of the 20th century.

It’s always such a pleasure to see academic figure studies such as these. One hopes that with the resurgence in classical training more will be gathered and put in books (along the lines of Ackerman’s wonderful Bargue reprint) or posted online.

I’m curious about painting not being taught in the Ecole until the 1860’s as this is well after the prix de Rome had been established, and obviously those winners could paint with exquisite skill. How was the training of painters structured outside the authority of the Ecole before that time? I had always thought the rise of independent painting atelier’s came later in the century. Any help with my confusion would be most welcome.

Oh and hi Elatia, nice to see you strolling in another park!

Amazing work and all so incredibly accomplished. It’s a shame their talents apparently remained “anonymous”. A lovely posting. Thank you for bringing them to light.