Today, I was looking through a collection of nineteenth-century Spanish Academic drawings–which I will explore at greater length in my next post–when I decided to take a break and read today’s Financial Times. In its “Collecting” section, the newspaper features the work of two “prodigious young British artists who capture the fractured experience of comtemporary life.” The contrast between the two sets of artists, nineteenth-century Spanish students and young contemporary British artists, could not be greater.

In her article “The P-Word,” critic Jackie Wullschlager writes about the painting Strange Solutions by Katy Moran (British, 1975), saying: “Vestiges of landscape or portrait forms persist alluringly. I detected a thick, snowy avenue . . . which briefly reminded me of Monet, and a human figure is suggested in deft gestural outline at the heart of the rococo brushwork . . .”

If art is a medium of communication and the artist is the communicator, then we are either playing a very poor game of telephone with Moran or the artist hopes that, like Navajo codebreakers, critics will interpret what they mean. For her part, Wullschlager will not commit to any ideas or feelings inspired by the work; not even being sure as to whether or not the works are portraits or landscapes. Instead she says it “reminds” or “suggests” something. I could go on, but my point, unlike the artists’ intent, is clear: this does not communicate, it confuses.

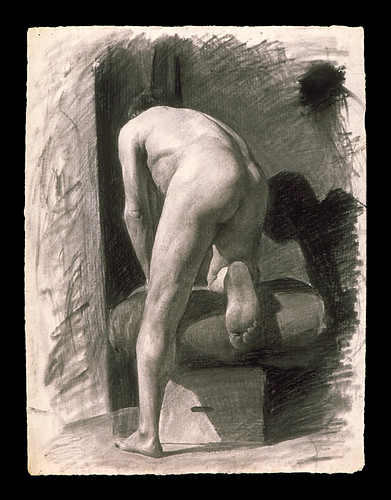

By comparison, the skills being taught to the Spanish student who created the “Study of an Adult Male,” are steeped in a tradition of clear communication. The artist is learning the vocabulary of the human figure, its structure and its range of motion. As a result, this artist will be able to place the figure in a wide array of narratives.

Much has been written about nineteenth-century academic training. For the most part, Modern to Contemporary artists and art historians dismissed the Academy and its strict teaching as oppressive to creative abilities and limited in its ability to communicate. As a result, they regularly discuss the Academy as if it were Goliath and the Impressionsists were David. All who followed David’s example of opposing the Academy were numbered among the Chosen People and all others were, by comparison, Philistines. But, I ask, is this evident in the fruits of either philosophy? Which generation of young artist seems more limited in its ability to communicate?

As my father often says, “Art is personal.” Personally, I am more stimulated and provoked to deeper thought and feeling by clear communication than by vague suggestions.

I am a recent follower of your extremely interesting blog, I just couldn’t agree more with your latest post.

Roman, I ask you: how likely is it that an “Elatia” and an “Ilaria” would make their way to your comments section regarding the same post? Our two names meaning different pitches of hugely overlapping states of being, that is. Are Letitia, Felicia and Allegra to follow? Maybe you’re about to get Muses…

But more to the point. A lot of 20th century painting boils down to painting about the possibilities of paint. This includes painting as suggestion rather than depiction. If the YBA painter has intended to suggest broadly enough that a viewer’s associations are actually what determines content — perception of content, that is — then she has succeeded rather than failed in her particular, and chosen, communication style. You are the art historian here, and I’m not, so this isn’t news to you. Neither does it lift the burden of dullness from the shoulders of the YBA whose work you cite — painting badly and succeeding in your communicative aims are not mutually exclusive.

The anonymous academic drawing you post here underlines the same point; it’s not a brilliant drawing but a 19th century figure study straight from Central Casting, fraught with no ambiguity whatsoever and all but impossible to misinterpret. (Yes, the figure COULD be leaning over to eat an ice cream cone so as not to drip on his tuffet, but…) To me — and I agree with you and your father that art is personal — the similarity of the YBA painting and the anonymous figure study is very great: each carries out the communicative intentions of the artist, neither is a high representative of its type.

What has changed unrecognizably in 150 years is the industry that surrounds art — the criticism industry, whose workers, from the late mid-20th century on, have been more in the position of auguring from innards than of writing about art. For art such as the painting above to have great meaning to anyone, some pretty fancy augury has to happen — is bound to happen, when the intentions of the artist are merely and openly to be an art world darling through the vehicle of painting, and the needs of the criticism industry are to celebrate few, trash many and comment much. Paintings like the YBA painting here desperately require this industry for reality — and vice versa. The drawing, by contrast, is what it is if it’s found in the street.

For me, the reasons to like the anonymous drawing, and its draftsman, are honesty and humility and the feeling of striving towards mastery that is conveyed. That is my reading of its greatest communicative value, and I do not need to find it excellent for it to have this value. There are masterpieces of the kind of painting posted here — suggestive non-objective painting that is deeply rewarding, that reaches into the heart and mind of the viewer without an assist from the criticism industry — but they may ask too much of viewers who are not predisposed to look at them. Thus, many feel rebuffed. But, is asking too much the same as failing to communicate?

I am so grateful for your thoughtful commentary, which adds enormously to what I hope to convey.

I love it. I completely agree on the subject and it could not be clearer. I wish I would of had professors whose personal teaching methods mirrored what is explained here.

Thank you,

Nicholas Coleman

Sorry, but I couldn’t disagree more. You keep saying that the picture of the person communicates clearly and thus is a better picture. Great artists throughout time though have fought against contrived cliched messages that everyone has heard a million times. They have strived to create new messages and new ways of communicating them. They are the reason that cultures thrive, grow, and transform. They fight against stagnation (artisticly and personally) and shame on you for dismissing their art as if it held no intrinsic value.

I am grateful for your comments and your willingness to share a contrary position.

In my experience new methods do not equal superior methods. As the Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg once noted ironically, “Of course, societies always progress. They never rot.” I do not believe that nineteenth-century painting is the end all and be all of art, nor do I believe that twentieth-century painting is without value.

To me, the use of the human figure in art–a staple of Academic theory–is not cliché (neither is it the only meaningful way of painting). It is the continuation of a tradition that includes Greco-Roman arts that were revived and carried through to the Renaissance until today. Considering the human figure in art as “cliché” is tantamount to dismissing the fundamentals of music theory and dismissing Western music composed or performed previous to Schoenberg. (Maybe that’s not what you are suggesting. If not, please clarify.)

The rejection of a tradition does not mean innovation. Rather, the artist who rejects it is required to create his or her own new tradition and corresponding vocabulary. Very few artists have been able to do that. (I would argue that Picasso was one who did.)

By pointing out words like “suggests” and “reminds” in the article, I was drawing attention to lack of clarity in intepreting the artist’s work. The critic was grasping at straws in an attempt to conjure meaning, let alone profundity. Is that too controversial? If so, so be it.

An elated Ilaria-again- and I apologize, as a foreigner, for not being able to match the eloquence of previous posters.

What I would like to highlight is that the drawing here is the work of a student, someone striving to aquire and master skills that can then open all possibilities of communication.

Those virtuoso skills reached their apex in 19th century atelier training before the advent of modernism and still taught to many modern artists.

In my “personal” view my favourite artists are those who have that ancient knowedge, for example impeccable draughtmanship, that somehow shines through their works even when they are simplified to the bone.

Virtuosism is what enchants me and I find it often lacking in contemporary artists, even in presence of an emotionally strong piece.

[…] laatst deze post tegen (op een zeer goed blog trouwens) dat alles een beetje samenvat imo. Consider a Contrast: Young Contemporary British Artist versus Nineteenth-Century Academic Student | … Een jonge Contemporary Artist 2007 Dit is oa wat ze je nu leren in kunstacademies. Spaanse […]

[…] the ‘previous generation’ of painters did- a projected epic layer of literature. As somebody in defense of traditionalism said about Katy Moran’s paintings: ’this does not […]

[…] the ‘previous generation’ of painters did- a projected epic layer of literature. As somebody in defense of traditionalism said about Katy Moran’s paintings: ’this does not […]

[…] the ‘previous generation’ of painters did- a projected epic layer of literature. As somebody in defense of traditionalism said about Katy Moran’s paintings: ’this does not […]