In a continuing series on painting frames, I would like to focus on a particular style: the tabernacle frame.

According to researchers at that National Gallery in Washington, the tabernacle frame grew out of devotional paintings. The architectural nature of the frame was meant to imitate the shape of a cathedral or church. As a result, the tabernacle frame was a portable religious site that could be put in a home or other private place of worship.

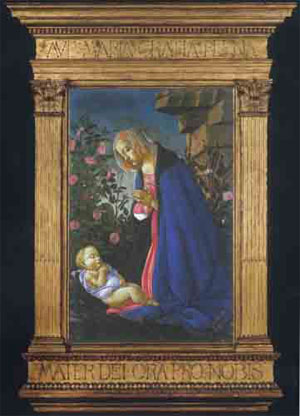

Like a church building, the make up of the frame consists of a plinth at the base and two columns surmounted by an entablature.

The earliest surviving examples of wooden tabernacle frames are from fifteenth-century Italy, where they were used in religious paintings, especially those featuring the Virgin and Christ Child.

(Some conservators, like those at the National Gallery in London, insist that Italian, pre-nineteenth-century frames should only be put on images with the Virgin and Christ Child.)

Though commissioned by collectors for older works, the tabernacle frame was rarely seen or used on contemporary paintings until the “Olympian painters” of Great Britain, especially Frederick Lord Leighton and Lawrence Alma-Tadema, began using them on their own paintings.

Leighton and Tadema separated the tabernacle frame from its religious context and used it to depict non-traditional scene. Both Leighton and Tadema often designed their own frames, and created unique approaches to the Greco-Roman architecture, especially Tadema, who chose Egyptian themes for many of his works and created frames to match.

Fascinating! This truly takes the secular painting outside the realm of the floating and membranous and anchors it in a completely separate reality, one almost as concrete as painting on a cassone or a harpsichord. In the Clark Institute in Williamstown, MA, there is a magnificent Steinway piano with decorative woodwork and painting designed by Alma-Tadema — the image-border ratio is about the same as in Cleopatra here. Thanks for another provocative post.