Note: Each week I hold a discussion with a group of professional artists on the development and career of a major artist. I post a video recording of each discussion. This week’s artist, Francisco de Goya y Lucientes, prompted an unusual amount of controversy. After reflecting on the thoughtful comments made by those who attended, I have decided to write a little reaction of my own here. The video can be found at the end of this post.

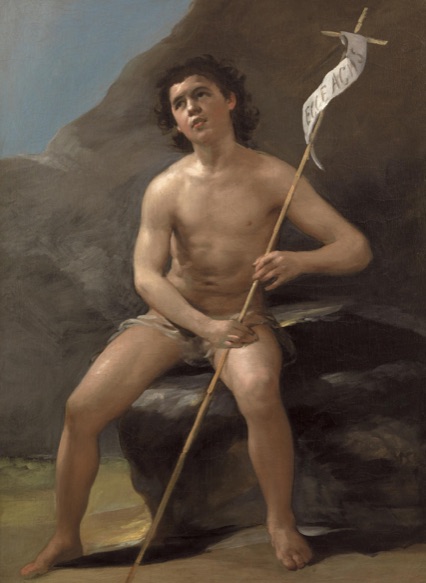

“The last Old Master and the first Modern painter” is an oft-repeated phrase used to describe Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (Spanish, 1746-1828). It captures the un-categorizable nature of Goya’s nearly seven-decades oeuvre, and hints at both his appreciation for the past and influence on those who came after. This week, I led two discussion on the development and career of the Spanish painter. Each gathering was heavily attended by professional artists, mostly traditionalists. I was surprised by the resistance experienced in comments and questions about Goya’s ability to paint.

For that reason, before posting video of the discussion, I would like to write a few words. First, to Modernists, who see Goya almost exclusively as a anti-traditionalist. And, secondly to traditionalists who are often unable to appreciate Goya’s remarkable craftsmanship. He does not belong solely to one team.

A few words about Goya for Modernists

In a 1921 essay titled “Tradition and the Individual Talent,” the poet TS Eliot, railed against the predominant spirit of his time, which he believed, saw originality as the highest value. Eliot did not see originality as innovation. In fact, he believed that innovation was dependent upon a solid understanding and appreciation of tradition:

We dwell with satisfaction upon the [artist’s] difference from his predecessors, especially his immediate predecessors; we endeavour to find something that can be isolated in order to be enjoyed. Whereas if we approach a poet without this prejudice we shall often find that not only the best, but the most individual parts of his work may be those in which the dead poets, his ancestors, assert their immortality most vigorously. And I do not mean the impressionable period of adolescence, but the period of full maturity. 1

Those who lionize Goya as having broken with tradition often ignore his portraits, religious and historical paintings and, instead, latch on to his experimental and private work, such as the so-called “Black Paintings” or etchings from the Disasters of War. While it is true that these works were revolutionary, they were also not usually intended for public consumption. Goya’s Black Paintings were made for the dining room in his private residence. And, the Disasters of War were not printed until some 35 years after his death. In other words, the artworks that we often see exclusively as representing Goya in art-history materials and courses were not the ones he was best known for in his own lifetime. I am not attempting to diminish the remarkable departure his experimental oeuvre represented at the time or their subsequent influence on artists. Looking only at his experimental works, Goya seems like a man out of time, almost completely divorced from the aesthetics of his time, which is not accurate.

A few words about Goya for Traditionalists

I have come to the conclusion that most artists interested in the classical tradition see Goya as unworthy of study. It is my belief this is not so much about whether or not his work is wanting. Goya is often excluded from the traditionalist lexicon because he was so well regarded by anti-traditional artists and modernists.

It is true that Goya’s influenced generations of artists seeking alternatives to Academic painting, most notably Gustave Courbet and Eduoard Manet. Yet, it is also true that over Goya’s nearly seven-decade career there were works, even very late in his career (e.g. The Spanish Consittution) that were traditional. As a young man, he worked alongside Anton Rafael Mengs. Under the German painter’s encouragement, Goya made a series of copper-plate etchings of works by Velázquez. Goya then went on to Italy on a kind of private prix de Rome, where he copied Greco-Roman statuary and produced an ambitious, large-scale history painting depicting Hannibal crossing the Alps.

In his portraiture, Goya could have hardly picked less polemical models to emulate:

“I have three masters: Nature, Velázquez, and Rembrandt.”

These are not the words of a anti-traditional revolutionary. Yet, it is my belief Goya has been treated lightly by traditionalists not necessarily because of his own work; but, because the Spanish artist was so well regarded by anti-traditional artists and modernists.

Goya’s timeline roughly parallels that of Jacques Louis David, David had established a strong, Neoclassical vision of art that dominated the French Academy and beyond. During the 1790s, while Goya was Professor of Painting at the Academia de San Fernando (Madrid), the taste for Neoclassicism led to heated debates on whether or not students in Spain should be held to new standards in terms of draughtsmanship and substitute their various Old-Master study materials — including artworks by Spanish, Flemish, and French artists — with those by Italian artists that more closely aligned with Neoclassical ideals, such as Raphael and Guercino. We have notes from the meeting where Goya stated his case for replacing pluralism with a nearly uniform style:

Finally, Sir, I cannot find another, more effective method for advancing the Arts, neither do I believe it exists, than to award and protect … the full liberty for genius to flow from those students of Art who want to learn [their instincts], without suppression, and without efforts to bend their inclination toward this or that style in Painting … 2

He was one of four professors at the Academia de Bellas Artes that voted, unsuccessfully, against the Neoclassicization of the Spanish Academy.

Does this mean Goya was “anti-academic”? I don’t believe so. In fact, I believe that Goya was attempting to preserve the Academy against itself. The strict adherence to towards Neoclassical dogma — one that arguably denied the Naturalism of Hellenistic sculpture — in European academies throughout the nineteenth century led to many schisms and misunderstandings about the nature of the Classical tradition.

If you are traditionalist or a portrait painter, I encourage you to look at Goya’s portraits. Last year, the National Gallery of London hosted the largest gathering of Goya’s portraits ever assembled in one place. It was astounding. I discuss is at length in the above video. (Skip ahead if you must).

Casado’s prescription for coming to terms with Goya

In 1882, the painter José Casado del Alisal was elected to the Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando the same school where Goya had taught nearly 100 years earlier. On that occasion, Casado attempted to describe to his colleagues — many of whom were still riding the anti-Goya wave of Neoclassicism and Neoplatonism — the value of Goya and his place within the pantheon of Spanish art:

Such a painter, so personal and impossible to copy, with his confident magnificence, with his strange and sublime eccentricities. He cannot have imitators, neither was he able to found a School. His genius was consummated with him …3

It is my hope that those who are anti-traditional can look at the entirety of Goya’s career and see where the Spanish artist subsumed and projected the traditions he inherited. Equally, I hope that Goya is welcomed with open arms by traditionalists, who may be surprised that they have unfairly ignored or marginalized a great master.

MJC

[cm_simple_form id=1]

- TS Eliot. “Tradition and the Individual Talent.” The Sacred Wood (1921)

- Francisco de Goya y Lucientes. Discurso a la Real Academia de San Fernando acerca de la forma de enseñar las artes plásticas. (Madrid: Real Academia de San Fernando, 1792). Original text: “Por último, Señor, yo no encuentro otro medio más eficaz de adelantar las Artes, ni creo que le haya, sino el de premiar y proteger al que despunte en ellas; el de dar mucha estimación al Profesor que lo sea; y el de dejar en su plena libertad correr el genio de los Discípulos que quieren aprenderlas, sino primir lo, ni poner medios para torcer la inclinación que manifiestan á este, o aquel, estilo, en la Pintura …”

- José Casado del Alisal. Discursos Leídos ante la Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando. (Madrid: Fortanet, 1885), 8. Full quote: “Goya, que ya recogiendo las pérdidas tradiciones, ó merced á la poderosa intuición de su alma, surge con fantasía y con fecundia inauditas, á romper las cadenas de la rutina; bastando, por si solo, á ilustra el último periodo de aquel siglo, con un arte nuevo y extraño, que, cuanto más se discute y más se estudia, con más fuerza se impone, por sus acento de verdad, por los arranques de su genialidad vigorosa y por su inspiración, reflejo de un alma intencionada y férrea, dotada de todas las energías de us raza aragonesa, que poco después dió al mundo en espectáculo en los gloriosos muros de la inmortal Zaragoza. Más, pintor tan personal y tan inimitable, en sus aciertos magníficos, como en sus extrañas y sublimes excentricidades, no podía tener imitadores, ni pudo fundar Escuela: su genio se consumió con él …”

Be First to Comment